October 7, 2013 — This article by Lawrence F Muscarella, PhD, is the second in a series of two and complements the first article, “Delayed reprocessing of gastrointestinal endoscopes and bronchoscopes,” which can be read by clicking here.

The more complete article (in PDF format) entitled “Revised instructions for pre-cleaning gastrointestinal endoscopes at bedside” on which this article herein is based may be downloaded by clicking here.

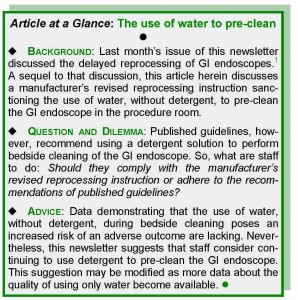

Briefly, this article – which discuss one manufacturer’s revised reprocessing instruction sanctioning the use of water, without detergent, to pre-clean GI endoscopes – answers the following question:

“Is it acceptable to use only water, without detergent, to ‘pre-clean’ gastrointestinal endoscopes at the patient’s bedside?”

♦

Published guidelines urge staff to reprocess the gastrointestinal (GI) endoscope promptly after its use.(1) Nevertheless, circumstances may arise that hinder adherence to this directive, abetting a backlog of soiled GI endoscopes and their delayed reprocessing as many as several hours after their clinical use.

These circumstances include an occasionally encountered “reprocessing bottleneck” and the unavailability of trained reprocessing staff, the latter of which may happen, for example, when GI endoscopy is performed “off hours.”(1)

While limited, some guidance about delayed reprocessing has been published.(1) In fact, one manufacturer of GI endoscopes condones it, provided, however, that a number of criteria are satisfied and caveats are understood.(1)

Defined as the cleaning and high-level disinfection of a soiled gastrointestinal (GI) endoscope more than one hour after its clinical use,(1) delayed reprocessing also may be applicable to other comparable types of flexible endoscopes and reusable medical instruments.

Two related articles by Dr. Muscarella:

Criteria, caveats

These criteria and caveats are discussed in the first article in this series of two (which may be read by clicking here), and they include the manufacturer’s requirement that several steps be performed to “prep,” or pre-treat, the GI endoscope in advance of its delayed reprocessing.(1)

These preparatory steps include “leak testing” and the prolonged immersion of the GI endoscope in a detergent solution (for up to 10 hours during the reprocessing hiatus). Once the reprocessing bottleneck is resolved or trained reprocessing staff become available, the GI endoscope is then cleaned and high-level disinfected as if its reprocessing had not been delayed.(1)

Quality and Safety Services and Case Reviews for Hospitals, Manufacturers, Patients: Click here to read about Dr. Muscarella’s quality and safety services committed to reducing the risk of healthcare-associated infections, including CRE outbreaks linked to contaminated endoscopes and other reusable medical equipment.

Step-by-step protocol

A protocol featuring each of these several steps and which may be suitable for prepping the GI endoscope is provided in another of Dr. Muscarella’s articles, which is available by clicking here.

This protocol may be suitable for prepping a soiled GI endoscope (or a comparable type of flexible endoscope or reusable medical instrument) in advance of its delayed reprocessing. The reader’s review of this protocol is recommended.

Delayed reprocessing may be permissible, provided the GI endoscope has been “prepped,” which includes its prolonged immersion in detergent. — Lawrence F Muscarella, PhD

No matter this protocol’s relative convenience or this manufacturer’s conditional condonation of delayed reprocessing, however, guidelines recommend the prompt reprocessing of GI endoscopes.(1) Otherwise, potentially infectious patient materials may dry and harden on the instrument’s surfaces, posing an increased risk of ineffective reprocessing and disease transmission, as well as of endoscope damage.

Bedside cleaning

Endoscope reprocessing may be divided into two sequential phases, based on the different locations within the medical facility where either is ordinarily performed.

1. Bedside cleaning, or pre-cleaning, of the GI endoscope (referred to as phase 1) is an initial set of practices that are performed in the procedure room immediately after the exam. These practices, which include flushing the GI endoscope’s water channel with water, are detailed in the box, just below.

2. Terminal reprocessing of the GI endoscope (referred to as phase 2), on the other hand, is a more comprehensive set of practices that are subsequently performed in the reprocessing room. These steps include the GI endoscope’s leak-testing, manual cleaning, high-level disinfection (at a minimum), and drying.(1)

When performed properly, in timely sequence, and as recommended by published guidelines, these two phases render a (well-maintained) GI endoscope safe for reuse, with virtually no risk of it transmitting disease.(1) Whereas the importance of using a detergent to clean GI endoscopes during terminal reprocessing (phase 2) is not debated, a manufacturer no longer requires that a detergent solution be used to pre-clean models of its GI endoscopes immediately following the exam, at bedside (phase 1).(2,3)

The prompt reprocessing of GI endoscopes is urged, to prevent the drying and hardening of patient materials that could pose an increased risk of patient-to-patient disease transmission.—Lawrence F Muscarella PhD

A revised reprocessing instruction

On February 19, 2010,(2) and December 13, 2011,(3) this manufacturer (Olympus America) announced via two written notices, respectively, that it had validated several practices to improve the efficiency of endoscope reprocessing. As a result of these improvements, this manufacturer accordingly revised the reprocessing manual of more than two dozen models of its 140-, 160-, and 180-series of upper and lower GI endoscopes.

One of these improvements was to no longer require that a detergent be used to pre-clean the GI endoscope in the procedure room (phase 1). For example, according to this manufacturer’s revised manual, the GI endoscope may be wiped during its pre-cleaning using a gauze, sponge or clean, lint-free cloth soaked with (fresh, clean) water, without detergent.*

[* Note: Notwithstanding its claim to have validated the use of water, the manufacturer states that staff may continue using a detergent solution during the GI endoscope’s bedside cleaning in accordance with the recommendations of published guidelines (phase 1).(4,5) Moreover, this manufacturer stresses the importance of always using detergent to clean the GI endoscope in the reprocessing room prior to high-level disinfection (phase 2).(2,3]

Some of the other improvements that this manufacturer of GI endoscopes included in its revised reprocessing manual were the addition of instructions for using this manufacturer’s “OFP” pump to flush the GI endoscope’s auxiliary water channel (with water) during pre-cleaning (in lieu of manually flushing this channel using a syringe as otherwise required).(2,3)

Question

In response to this manufacturer’s notices and revised reprocessing manual,(2,3) readers of Dr. Muscarella’s writings asked whether using water, without detergent, to pre-clean the GI endoscope is suitable, or whether it remains advisable for staff to continue to adhere to any one of several published guidelines(4,5) that recommend using water and detergent during bedside cleaning as described in the box, above.(4,5)

Response

The reply to this question (provided herein) dovetails with, and is a sequel to, the discussion about the delayed reprocessing of GI endoscopes that is featured in another article, which can be read by clicking here.(1)

From a quality perspective, trained staff’s compliance with one—whether the manufacturer’s revised instruction (to use water without detergent) or the guidelines’ recommendation (to use a detergent solution)—would be a deviation that lacks consistency and conformity vis-à-vis the other.

Briefly, a “deviation” in this context is defined as an instrument-reprocessing practice that departs from an infection-control standard or a validated procedure. Although a non-conformance with the potential to adversely impact quality, a deviation in reprocessing may, but does not necessarily, pose an increased risk of patient harm.

In general, the identification of a deviation in reprocessing (during, for example, an accreditation survey) would typically result in management’s assessment of the deviation’s risk of disease transmission, determination of the deviation’s potential contributing factors and root causes, and implementation of one or more actions designed to correct the deviation (for example, the re-training of reprocessing staff). But, in this discussion, which is the deviation:

- staff’s adherence to the manufacturer’s revised reprocessing manual; or,

- staff’s compliance with the recommendations of published guidelines?

A deviation in instrument reprocessing may be defined as a departure from an infection-control standard or a validated procedure. — Lawrence F Muscarella, PhD

Discussion

The answer to this question and whether it is advisable for staff to use a detergent solution, or only water, to pre-clean GI endoscopes is not straightforward or self-evident. On the one hand, it could be reasonably argued that, although sanctioned in this manufacturer’s revised manual, not using detergent during the bedside cleaning of GI endoscopes is the deviation, because, as previously noted, this practice contravenes published reprocessing guidelines, which specifically advise using a detergent solution to pre-clean GI endoscopes.(4,5)

To be sure, published reports have identified the improper reprocessing of GI endoscopes as the cause of the transmission of infectious agents, with associated morbidity and mortality.4-7 —Lawrence F Muscarella, PhD

(Other considerations that might suggest that the use of water, without detergent, is a deviation include the description of these initial cleaning steps performed in the procedure room, not as bedside-watering, but as bedside cleaning, which manifestly implies the use of a detergent. Also, this manufacturer’s revised instruction eliminates a reprocessing practice; it does not add a safety measure.)

A manufacturer’s prerogative

On the other hand, the revision of a device’s label or reprocessing instructions is generally the manufacturer’s prerogative. Such a change is usually meritorious, and, if adequately validated, the change may establish a new, safe standard.

Staff’s compliance with a manufacturer’s instruction that conflicts with a guideline’s recommendation is not necessarily a de facto deviation. It is possible that the manufacturer’s elimination in its revised manual of the requirement that a detergent be used to pre-clean the GI endoscope, which the manufacturer describes as a “validated” improvement,(2,3) does not compromise safety.

Quality and Safety Services and Case Reviews for Hospitals, Manufacturers, Patients: Click here to read about Dr. Muscarella’s quality and safety services committed to reducing the risk of healthcare-associated infections, including CRE outbreaks linked to contaminated endoscopes and other reusable medical equipment.

Regulatory oversight of labeling changes

Seemingly in support of the soundness of this manufacturer’s revised reprocessing manual, reports (to date) have not associated the exclusive use of water (without detergent) to pre-clean the GI endoscope with an adverse outcome.

Nevertheless, while it is generally at the manufacturer’s behest (e.g., unless mandated by a regulatory agency), the revision of a device’s labeling or reprocessing manual, like a modification to the device’s design, requires control as prescribed by the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Quality System (QS) regulation,(8,9) a discussion of which is provided in another article, which is available by clicking here.

Changes to a device’s labeling that lack the necessary control could render the device adulterated and misbranded — Lawrence F. Muscarella PhD

There are instances for which a change to its device’s labeling (or design) is minor and requires that the manufacturer exercise only limited control, without regulations requiring that the FDA review and approbate the change.

In other instances, however, federal regulations require additional control and that the manufacturer inform the FDA of the change, via a pre-market notification, prior to marketing the device.

At times a source of confusion for manufacturers, the regulatory significance and impact of a specific labeling change and whether it requires a new 510(k) clearance may not always be obvious.

Reprocessing instructions are an important feature of a GI endoscope’s labeling and performance, and, as a general rule, if a change to these instructions is significant with the potential to adversely affect the device’s safety and effectiveness, then the FDA would most likely require additional control and that the device receive a new 510(k) clearance.

At times a source of confusion for manufacturers, the regulatory significance and impact of a specific labeling or design change, and whether it requires a new 510(k) clearance, may not always be obvious. — Lawrence F Muscarella PhD

A “major” change?

This manufacturer’s announcement (via two notices) that it had “validated”2,3 the use of water (without detergent) to pre-clean the GI endoscope reasonably suggests that this manufacturer concluded that this revised reprocessing instruction is a minor change, requiring only limited control in accordance with the FDA’s Quality System Regulation.(8)

Warranting consideration, however, the FDA could plausibly conclude (as with any design or labeling change) that this is a “major” labeling change9 with the potential to significantly impact the device’s safety and effectiveness, therefore requiring additional control, namely, that the GI endoscope receive a new 510(k) clearance.*

[* Note: If the manufacturer’s rationale for revising the reprocessing instructions of a reusable instrument was based on an adverse event or customer complaints about the instrument; a failure mode analysis the manufacturer performed; or corrective actions the manufacturer issued, then the FDA may consider the label’s revision a “major change” requiring not just validation that the change does not adversely impact the reusable instrument’s safety and effectiveness, but, additionally, that the device receive a new 510(k) clearance.(9)]

The improper control of a device’s label or reprocessing instructions may have potentially adverse consequences that are not limited to the manufacturer and may also include the medical facility. — Lawrence F Muscarella, PhD

The potentially adverse consequences of the improper control of a change to a device’s design or labeling are not limited to the manufacturer—they may also impact the medical facility. The FDA may conclude that a device whose reprocessing instructions were changed significantly, but that did not receive a new 510(k) clearance (or pre-market approval), is adulterated and mis-branded, which could pose legal risk for a medical facility that uses the modified device.

(One recent regulatory action about which readers are likely familiar underscores the significance of a medical device’s reprocessing instructions and changes to them. With as much national impact on instrument reprocessing as any other recent regulatory action, the FDA determined in 2009 that the STERIS System 1 [SS1] had been modified and without a 510[k] clearance or pre-market approval since 1988.(10-12)

As a consequence, the FDA concluded in 2010, that rigid endoscopes and any other reusable device whose labeling referenced the SS1 as a suitable, compatible, or recommended method for the device’s reprocessing became themselves mis-branded, like the SS1, for failing to provide adequate instructions for use as federal regulations require.(12))

Recommendations

Consistent with published guidelines,(4,5) it is suggested that medical facilities consider continuing to use detergent to pre-clean the GI endoscope at bedside (at least) until more data are published independently confirming the suitability of using only water for this purpose.

To be sure, effective bedside-cleaning is important to initiate the cleaning process, prevent the drying and hardening of potentially infectious patient materials on the GI endoscope’s surfaces, and minimize the risk of infection,(1)

Alternatively, however, if a medical facility elects to comply with the manufacturer’s revised instruction and uses water, without detergent, to pre-clean the GI endoscope, a practice that has not been reported to pose an increased risk of patient harm, then this article suggests that the medical facility consider requesting from the manufacturer a written statement (independent of the manufacturer’s aforementioned notices) certifying that this revision of its reprocessing manual is a minor change that neither adversely affects the GI endoscope’s safety and/or effectiveness nor adulterates and/or misbrands the GI endoscope (or, alternatively, acknowledging that this change was significant and that the FDA granted a new 510(k) clearance for each of the models of GI endoscopes that were the subject of the manufacturer’s notices).

References: This article’s references are available by clicking here.

Article by: Lawrence F Muscarella, PhD, posted on 3-6-2013; updated 10/1/2015, Rev A.